Platelet

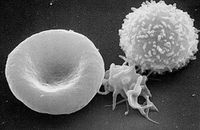

Platelets, or thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος — «clot» and κύτος — «cell»), are small, irregularly-shaped anuclear cell fragments (i.e. cells that do not have a nucleus containing DNA), 2-3 µm in diameter[1], which are derived from fragmentation of precursor megakaryocytes. The average lifespan of a platelet is normally just 5 to 9 days. Platelets play a fundamental role in hemostasis and are a natural source of growth factors. They circulate in the blood of mammals and are involved in hemostasis, leading to the formation of blood clots.

If the number of platelets is too low, excessive bleeding can occur. However, if the number of platelets is too high, blood clots can form (thrombosis), which may obstruct blood vessels and result in such events as a stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism or the blockage of blood vessels to other parts of the body, such as the extremities of the arms or legs. An abnormality or disease of the platelets is called a thrombocytopathy[2], which could be either a low number of platelets (thrombocytopenia), a decrease in function of platelets (thrombasthenia), or an increase in the number of platelets (thrombocytosis). There are disorders that reduce the number of platelets, such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) that typically cause thromboses, or clots, instead of bleeding.

Platelets release a multitude of growth factors including Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), a potent chemotactic agent, and TGF beta, which stimulates the deposition of extracellular matrix. Both of these growth factors have been shown to play a significant role in the repair and regeneration of connective tissues. Other healing-associated growth factors produced by platelets include basic fibroblast growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, platelet-derived epidermal growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Local application of these factors in increased concentrations through Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been used as an adjunct to wound healing for several decades[3][4][5][6][7][8][9].

Contents |

Kinetics

- Platelets are produced in blood cell formation (thrombopoiesis) in bone marrow, by budding off from megakaryocytes.

- The physiological range for platelets is 150-400 x 109 per liter.

- Around 1 x 1011 platelets are produced each day by an average healthy adult.

- The lifespan of circulating platelets is 5 to 9 days.

- Megakaryocyte and platelet production is regulated by thrombopoietin, a hormone usually produced by the liver and kidneys.

- Each megakaryocyte produces between 5,000 and 10,000 platelets.

- Old platelets are destroyed by phagocytosis in the spleen and by Kupffer cells in the liver.

- A reserve of platelets are stored in the spleen and are released when needed by sympathetically-induced splenic contraction.

Thrombus formation

The function of platelets is the maintenance of hemostasis. This is achieved primarily by the formation of thrombi, when damage to the endothelium of blood vessels occurs. On the converse, thrombus formation must be inhibited at times when there is no damage to the endothelium.

Activation

The inner surface of blood vessels is lined with a thin layer of endothelial cells that, in normal hemostasis, acts to inhibit platelet activation by producing nitric oxide, endothelial-ADPase, and PGI2. Endothelial-ADPase clears away the platelet activator, ADP.

Endothelial cells produce a protein called von Willebrand factor (vWF), a cell adhesion ligand, which helps endothelial cells adhere to collagen in the basement membrane. Under physiological conditions, collagen is not exposed to the bloodstream. vWF is secreted constitutively into the plasma by the endothelial cells, and is stored in granules within the endothelial cell and in platelets.

When the endothelial layer is injured, collagen, vWF and tissue factor from the subendothelium is exposed to the bloodstream. When the platelets contact collagen or vWF, they are activated (eg. to clump together). They are also activated by thrombin (formed with the help of tissue factor). They can also be activated by a negatively-charged surface, such as glass.

Platelet activation further results in the scramblase-mediated transport of negatively-charged phospholipids to the platelet surface. These phospholipids provide a catalytic surface (with the charge provided by phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine) for the tenase and prothrombinase complexes. Calcium ions are essential for binding of these coagulation factors.

Shape change

Activated platelets change in shape to become more spherical, and pseudopods form on their surface. Thus they assume a stellate shape.

Granule secretion

Platelets contain alpha and dense granules. Activated platelets excrete the contents of these granules into their canalicular systems and into surrounding blood. There are three types of granules:

- delta granules (containing ADP or ATP, calcium, and serotonin)

- lamda granules - similar to lysosomes and contain several hydrolytic enzymes.

- α-granules (containing platelet factor 4, transforming growth factor-β1, platelet-derived growth factor, fibronectin, B-thromboglobulin, vWF, fibrinogen, and coagulation factors V and XIII).

Thromboxane A2 synthesis

Platelet activation initiates the arachidonic acid pathway to produce TXA2. TXA2 is involved in activating other platelets and its formation is inhibited by COX inhibitors, such as aspirin.

Adhesion and aggregation

Platelets aggregate, or clump together, using fibrinogen and vWF as a connecting agent. The most abundant platelet aggregation receptor is glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (gpIIb/IIIa); this is a calcium-dependent receptor for fibrinogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, thrombospondin, and von Willebrand factor (vWF). Other receptors include GPIb-V-IX complex (vWF) and GPVI (collagen).

Activated platelets will adhere, via glycoprotein (GP) Ia, to the collagen that is exposed by endothelial damage. Aggregation and adhesion act together to form the platelet plug. Myosin and actin filaments in platelets are stimulated to contract during aggregation, further reinforcing the plug.

Platelet aggregation is stimulated by ADP, thromboxane, and α2 receptor-activation, but inhibited by other inflammatory products like PGI2 and PGD2. Platelet aggregation is enhanced by exogenous administration of anabolic steroids.

Wound repair

The blood clot is only a temporary solution to stop bleeding; vessel repair is therefore needed. The aggregated platelets help this process by secreting chemicals that promote the invasion of fibroblasts from surrounding connective tissue into the wounded area to form a scar. The obstructing clot is slowly dissolved by the fibrinolytic enzyme, plasmin, and the platelets are cleared by phagocytosis.

Other functions

- Clot retraction

- Pro-coagulation

- Inflammation

- Cytokine signalling

- Phagocytosis[10]

Cytokine signaling

In addition to being the chief cellular effector of hemostasis, platelets are rapidly deployed to sites of injury or infection, and potentially modulate inflammatory processes by interacting with leukocytes and by secreting cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators[11] [12] [13] [14]. Platelets also secrete platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).

Role in disease

High and low counts

A normal platelet count in a healthy individual is between 150,000 and 450,000 per μl (microlitre) of blood (150–450 x 109/L)[15]. Ninety-five percent of healthy people will have platelet counts in this range. Some will have statistically abnormal platelet counts while having no demonstrable abnormality. However, if it is either very low or very high, the likelihood of an abnormality being present is higher.

Both thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis may present with coagulation problems. In general, low platelet counts increase bleeding risks; however there are exceptions. For example, immune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis (high counts) may lead to thrombosis, although this is mainly when the elevated count is due to myeloproliferative disorder.

Low platelet counts are, in general, not corrected by transfusion unless the patient is bleeding or the count has fallen below 5 x 109/L. Transfusion is contraindicated in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), as it fuels the coagulopathy. In patients undergoing surgery, a level below 50 x 109/L is associated with abnormal surgical bleeding, and regional anaesthetic procedures such as epidurals are avoided for levels below 80-100.

Normal platelet counts are not a guarantee of adequate function. In some states, the platelets, while being adequate in number, are dysfunctional. For instance, aspirin irreversibly disrupts platelet function by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-1 (COX1), and hence normal hemostasis. The resulting platelets are unable to produce new cyclooxygenase because they have no DNA. Normal platelet function will not return until the use of aspirin has ceased and enough of the affected platelets have been replaced by new ones, which can take over a week. Ibuprofen, another NSAID, does not have such a long duration effect, with platelet function usually returning within 24 hours[16], and taking ibuprofen before aspirin will prevent the irreversible effects of aspirin[17]. Uremia, a consequence of renal failure, leads to platelet dysfunction that may be ameliorated by the administration of desmopressin.

Medications

Oral agents, often used to alter/suppress platelet function:

- aspirin

- clopidogrel

- cilostazol

- ticlopidine

Intravenous agents, often used to alter/suppress platelet function:

- abciximab

- eptifibatide

- tirofiban

Diseases

Disorders leading to a reduced platelet count:

- Thrombocytopenia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura - also known as immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Drug-induced thrombocytopenic purpura (for example heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT))

- Gaucher's disease

- Aplastic anemia

Alloimmune disorders

- Fetomaternal alloimmune thrombocytopenia

- Some transfusion reactions

Disorders leading to platelet dysfunction or reduced count:

- HELLP syndrome

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome

- Chemotherapy

- Dengue

Disorders featuring an elevated count:

- Thrombocytosis, including essential thrombocytosis (elevated counts, either reactive or as an expression of myeloproliferative disease); may feature dysfunctional platelets

Disorders of platelet adhesion or aggregation:

- Bernard-Soulier syndrome

- Glanzmann's thrombasthenia

- Scott's syndrome

- von Willebrand disease

- Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome

- Gray platelet syndrome

Disorders of platelet metabolism

- Decreased cyclooxygenase activity, induced or congenital

- Storage pool defects, acquired or congenital

Disorders that indirectly compromise platelet function:

Disorders in which platelets play a key role:

- Atherosclerosis

- Coronary artery disease, CAD and myocardial infarction, MI

- Cerebrovascular disease and Stroke, CVA (cerebrovascular accident)

- Peripheral artery occlusive disease (PAOD)

- Cancer [18]

| Condition | Prothrombin time | Partial thromboplastin time | Bleeding time | Platelet count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K deficiency or warfarin | prolonged | prolonged | unaffected | unaffected |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | prolonged | prolonged | prolonged | decreased |

| Von Willebrand disease | unaffected | prolonged | prolonged | unaffected |

| Haemophilia | unaffected | prolonged | unaffected | unaffected |

| Aspirin | unaffected | unaffected | prolonged | unaffected |

| Thrombocytopenia | unaffected | unaffected | prolonged | decreased |

| Early Liver failure | prolonged | unaffected | unaffected | unaffected |

| End-stage Liver failure | prolonged | prolonged | prolonged | decreased |

| Uremia | unaffected | unaffected | prolonged | unaffected |

| Congenital afibrinogenemia | prolonged | prolonged | prolonged | unaffected |

| Factor V deficiency | prolonged | prolonged | unaffected | unaffected |

| Factor X deficiency as seen in amyloid purpura | prolonged | prolonged | unaffected | unaffected |

| Glanzmann's thrombasthenia | unaffected | unaffected | prolonged | unaffected |

| Bernard-Soulier syndrome | unaffected | unaffected | prolonged | decreased |

Discovery

Brewer[19] traced the history of the discovery of the platelet. Although red blood cells had been known since van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), it was the German anatomist Max Schultze (1825-1874) who first offered a description of the platelet in his newly-founded journal Archiv für mikroscopische Anatomie[20]. He describes "spherules" to be much smaller than red blood cells that are occasionally clumped and may participate in collections of fibrous material. He recommends further study of the findings.

Giulio Bizzozero (1846-1901), building on Schultze's findings, used "living circulation" to study blood cells of amphibians microscopically in vivo. He is especially noted for discovering that platelets clump at the site of blood vessel injury, a process that precedes the formation of a blood clot. This observation confirmed the role of platelets in coagulation[21].

In transfusion medicine

Platelets are either isolated from collected units of whole blood and pooled to make a therapeutic dose or collected by apheresis, sometimes concurrently with plasma or red blood cells. The industry standard is for platelets to be tested for bacteria before transfusion to avoid septic reactions, which can be fatal.

Pooled whole-blood platelets, sometimes called "random" platelets, are made by taking a unit of whole blood that has not been cooled and placing it into a large centrifuge in what is referred to as a "soft spin." This splits the blood into three layers: the plasma, a "buffy coat" layer, which includes the platelets, and the white blood cells. These are expressed into different bags for storage.

Apheresis platelets are collected using a mechanical device that draws blood from the donor and centrifuges the collected blood to separate out the platelets and other components to be collected. The remaining blood is returned to the donor. The advantage to this method is that a single donation provides at least one therapeutic dose, as opposed to the multiple donations for whole-blood platelets. This means that a recipient is not exposed to as many different donors and has less risk of transfusion-transmitted disease and other complications. Sometimes a person such as a cancer patient that requires routine transfusions of platelets will receive repeated donations from a specific donor to further minimize the risk.

Platelets are not cross-matched unless they contain a significant amount of red blood cells (RBCs), which results in a reddish-orange color to the product. This is usually associated with whole-blood platelets, as apheresis methods are more efficient than "soft spin" centrifugation at isolating the specific components of blood. An effort is usually made to issue type specific platelets, but this is not as critical as it is with RBCs.

Platelets collected by either method have a very short shelf life, typically five or seven days depending on the system used. This results in frequent problems with short supply, as testing the donations often requires up to a full day. Since there are no effective preservative solutions for platelets, they lose potency quickly and are best when fresh.

Platelets, either apheresis or random-donor platelets, can be processed through a volume reduction process. In this process, the platelets are spun in a centrifuge and the excess plasma is removed, leaving 10 to 100 ml of platelet concentrate. Volume-reduced platelets are normally transfused only to neonatal and pediatric patients when a large volume of plasma could overload the child's small circulatory system. The lower volume of plasma also reduces the chances of an adverse transfusion reaction to plasma proteins.[22] Volume reduced platelets have a shelf life of only four hours.[23]

See also

- Hemostasis

- Plateletpheresis

References

- ↑ Campbell, Neil A. (2008). Biology (8th ed.). London: Pearson Education. p. 912. ISBN 978-0-321-53616-7. "Platelets are pinched-off cytoplasmic fragments of specialized bone marrow cells. They are about 2-3µm in diameter and have no nuclei. Platelets serve both structural and molecular functions in blood clotting."

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins, Charles William McLaughlin, Susan Johnson, Maryanna Quon Warner, David LaHart, Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ O’Connell S, Impeduglia T, Hessler K, Wang XJ, Carroll R, Dardik H. Autologous platelet-rich fibrin matrix as cell therapy in the healing of chronic lower-extremity ulcers. Wound Rep Reg 2008; 16:749-756.

- ↑ Sánchez M, Anitua E, Azofra J, Andía I, Padilla S, Mujika I. Comparison of surgically repaired Achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2007; 35 (2): 245-51.

- ↑ Knighton DR, Ciresi KF, Fiegel VD, Austin LL, Butler ELL. Classification and treatment of chronic nonhealing wounds: successful treatment with autologous platelet-derived wound healing factors (PDWHF). Ann surg 1986; 204:322-30.

- ↑ Knighton DR, Ciresi K, Fiegel VD, Schumerth S, Butler E, Cerra F. Stimulation of repair in chronic, non healing, cutaneous ulcers using platelet-derived wound healing formula. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1990; 170:56-60.

- ↑ Celotti F, Colciago A, Negri-Cesi P, Pravettoni A, Zaninetti R, Sacchi MC. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on migration and proliferation of SaOS-2 osteoblasts: role of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-β. Wound Rep Regen 2006; 14:195-202.

- ↑ McAleer JP, Sharma S, Kaplan EM, Perisch G. Use of autologous platelet concentrate in a nonhealing lower extremity wound. Adv Skin Wound Care 2006; 19:354-63.

- ↑ Driver VR, Hanft J, Fylling CP, Beriou JM. Arospective, randomized, controlled trial of autologous platelet-rich plasma gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 2006;52:68-87.

- ↑ Movat H.Zet al.; Weiser, WJ; Glynn, MF; Mustard, JF (1965). "Platelet Phagocytosis and Aggregation". Journal of Cell Biology 27 (3): 531–543. doi:10.1083/jcb.27.3.531. PMID 4957257.

- ↑ Weyrich A.S. et al. (2004). "Platelets: signaling cells inside the immune continuum.". Trends Immunol 25: 489–495.

- ↑ Wagner D.D. et al. (2003). "Platelets in inflammation and thrombosis.". Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 2131–2137.

- ↑ Diacovo T.G. et al. (1996). "Platelet-mediated lymphocyte delivery to high endothelial venules.". Science 273: 252–255.

- ↑ Iannacone M. et al. (2005). "Platelets mediate cytotoxic T lymphocyte-induced liver damage". Nat Med 11: 1167–1169.

- ↑ Kumar & Clark (2005). "8". Clinical Medicine (Sixth ed.). Elsevier Saunders. pp. 469. ISBN 0702027634.

- ↑ "Platelet Function after Taking Ibuprofen for 1 Week". http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/142/7/I-54. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ "Ibuprofen protects platelet cyclooxygenase from irreversible inhibition by aspirin". http://atvb.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/3/4/383. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Erpenbeck L, Schön MP (April 2010). "Deadly allies: the fatal interplay between platelets and metastasizing cancer cells". Blood 115 (17): 3427–36. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-10-247296. PMID 20194899.

- ↑ Brewer DB. Max Schultze (1865), G. Bizzozero (1882) and the discovery of the platelet. Br J Haematol 2006;133:251-8. PMID 16643426.

- ↑ Schultze M. Ein heizbarer Objecttisch und seine Verwendung bei Untersuchungen des Blutes. Arch Mikrosc Anat 1865;1:1-42.

- ↑ Bizzozero J. Über einen neuen Forrnbestandteil des Blutes und dessen Rolle bei der Thrombose und Blutgerinnung. Arch Pathol Anat Phys Klin Med 1882;90:261-332.

- ↑ Schoenfeld H, Spies C, Jakob C (2006). "Volume-reduced platelet concentrates". Curr. Hematol. Rep. 5 (1): 82–8. PMID 16537051.

- ↑ CBBS: Washed and volume-reduced Plateletpheresis units

External links

- The Platelet Forum A site where researchers can discuss their work and multimedia relating to platelets.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||